Warren Buffett Steps Down: What’s Next for Berkshire Hathaway?

Why the end of an era could be good news for investors.

“Graveyards are full of indispensable people,” Charles de Gaulle, French war hero (of both World Wars) and former president of France, and many others have observed in one iteration or another about the human condition. The observation is no sentimental lament, it’s dismissive cynicism.

After we’re gone, most of us are relegated to a back-burner memory conjured by happenstance. Only those with whom we are most intimate — a spouse, a child, a parent — will remember to the end, and even their memory and longing will dim with time. When we depart the material world, our role will be assumed by another, and much sooner than we are comfortable contemplating.

But why wait until the ultimate goodbye?

Evidence of our dispensability while we’re extant is apparent everywhere: sports, politics, religion, entertainment, science. No matter how sublime we were perceived at a point in time, once out of sight, soon out of mind. The world gets on with it, whether we’re missing in spirit or body.

Business is no different. John D. Archbold supplants John D. Rockefeller at Standard Oil, Thomas Watson Jr. supplants Thomas Watson Sr. at IBM, Tim Cook supplants Steve Jobs, Andy Jassey supplants Jeff Bezos, Satya Nadella supplants Bill Gates (technically, Steve Ballmer supplanted Gates. Ballmer was a mulligan), and the earth continues to circle the sun, nonetheless.

At the moment it can seem otherwise. When the changing (or the impending change) of the guard occurs, many of us become addled by recency: “This time is different. I know it is. How can we possibly get along (without him or her)?”

No chief executive has been perceived as more indispensable than Warren Buffett. The perception isn’t wrong, as it wasn’t wrong with Rockefeller at Standard Oil, Gates at Microsoft, et al. They set the culture, established the processes, recognized the opportunities, forced the action to achieve the goals. Had they not existed neither would their respective enterprises.

But nothing remains in childhood, overseen by the guardian, in perpetuity. Dependency on the indispensable person recedes over time, as a child’s dependency on a parent recedes, thus rendering the indispensable dispensable. If it were otherwise, nothing would exist.

When the founder is indeed indispensable, it all dies with the founder. Sole proprietorships are the ready example. For any company with an established product or service, a managerial team, a market presence, a roster of employees, it’s rarely the case. Any founder worth his salt plans for continuity.

Perhaps investors ignored this live detail on May 3 during Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder extravaganza. It all concluded with what I thought was the most subdued of mic-drops: Warren Buffett confirming the most open of secrets, announcing he would step down as CEO at the end of the year and would recommend to the board (“recommend” a euphemism for fait accompli) that long-groomed co-chairman Greg Abel assume the role. I found Buffett’s announcement no more revelatory than if had he announced night follows day.

Perhaps I was in the minority. Berkshire shares dropped at the market open on the Monday following the announcement. They have been meandering about since.

I’ll concede that I could be wrong associating causality — that A caused B. Berkshire Hathaway shares were up 18% year to date before then. They were up 23% over the past 12 months. The S&P 500 — Berkshire’s benchmark — registered flat for the year. It was only 12% over the past 12 months. A balancing of the books might be all there was to it. Then again, I could be right.

Each individual’s bespoke skills are the product of time, environment, parentage, experiences, friends, beliefs, intelligence, perceptions, education, and temperament. Like snowflakes, no two combinings of the variables will duplicate. It’s true; there will never be another Warren Buffett, as too many financial columnists eulogized after Buffett publicly handed the board of directors his resignation. The observation is hardly profound. On the contrary, it is to belabor the obvious. There will never be another anyone, and that’s OK.

The world doesn’t need another Warren Buffett any more than it needs another William Shakespeare, Leonardo di Vinci, Isaac Newton, Voltaire, Albert Einstein, Ernest Hemingway, Elvis Presley, and anyone of notoriety (and, for that matter, anyone of no notoriety) whose name we can conjure. Been there, done that. Epigones never approach the success of the original. Led Zeppelin or the Led Zeppelin tribute band?

So let’s engage in a little deductive reasoning: Berkshire doesn’t need another Warren Buffett, and at this stage in its evolution it even needs less of the original. Buffett’s bespoke skills to accumulate businesses — wholly and partially owned — were instrumental to Berkshire’s success thirty years ago. I aver this skill to bolt on and incorporate is less instrumental today to that success. On the contrary, it may be detrimental.

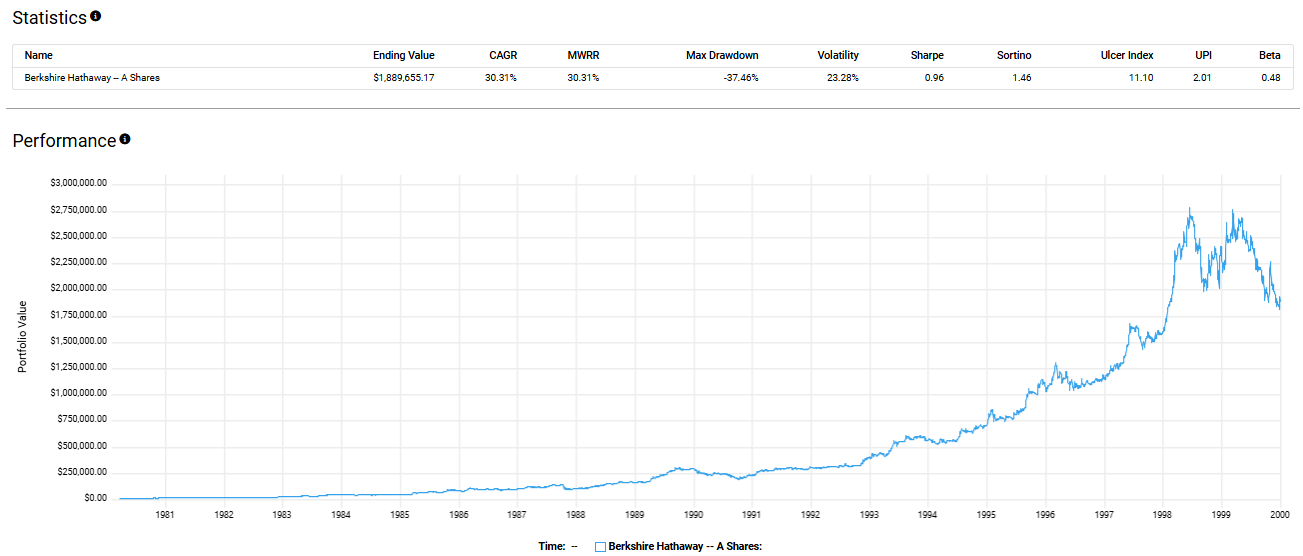

Berkshire Hathaway shares (“A”) generated a 30% CAGR over the 20 years from 1980 to 2000. (The first half was responsible for most of the heavy lifting, but not all. The CAGR was 20% through the 1990s.) The late 1988s brought the most celebrated windfall that that time: Berkshire’s Coca-Cola (KO) investment.

Berkshire Hathaway rolls into the new millennium considerably beefier than when it rolled into the 1980s. The share price has been brake-checked repeatedly, punctuated with sustained episodes of underperformance. The CAGR for the past 25 has been 11%, about a percentage point better than the S&P for the period, but a fair distance from what it was the prior 20 years.

Size, of course, is a problem of physics. The successful bolt-ons and incorporations have produced a lot of heft. Berkshire’s market cap tips the beams at over $1 trillion, placing it in a club whose members number fewer than the club composed of moonwalkers. I suppose it’s a blessing; it’s also a conundrum: Forty years ago, Buffett and Berkshire might consider a few hundred opportunities that could move the needle. Today, they might be lucky to consider 10.

It’s for wont of trying. Berkshire frequently rearranges the patio furniture over the course of a year. Stocks come and go with little fanfare: investments in the hundreds of millions or a couple of billions of dollars are sold and replaced with another of like size. On the high end, we might find a Chubb Limited (CB). Berkshire purchased $6.7 billion worth of the P&C insurer’s stock in the first quarter of 2024. The stake is worth $8.0 billion today.

Success has been found on the other side of the Pacific. Berkshire began to invest in Japan in the summer of 2019. A year later it announced it had accumulated 5% stakes in five Japanese trading houses: Itochu Corp., Marubeni Corp., Mitsubishi Corp., Mitsui & Co., and Sumitomo Corp. Berkshire has incrementally added to the quintet, investing $13.8 billion to date (as far as we know). The stake is worth $24 billion today.

Berkshire spent $15 billion this decade buying Chevron (CVX) shares. It has approximately $27 billion — stock, preferred stock, and warrants — invested in Occidental Petroleum (OXY). Both companies’ shares have underperformed industry leader ExxonMobil (XOM).

And then there is Apple (AAPL).

Berkshire began accumulating Apple shares in the first quarter of 2016. It continued to accumulate the shares over the subsequent two years. When all was said and done, Berkshire had invested $40 billion in Apple' stock. At the peak, in December 2023, Berkshire’s stake was worth $178 billion and accounted for 49% of the market value of Berkshire’s stock portfolio. A prudent downsizing followed. The stake accounts for approximately 26% of the market value of the portfolio today.

(Sidebar: I find Berkshire’s Apple investment intriguing on many levels. When Buffett commenced buying Apple shares for Berkshire’s account, Apple was the largest publicly traded company by market cap. This was no recondite fly-under-the-radar investment. What’s more, the shares had appreciated 140% over the prior five years. The shares weren’t especially cheap or dear based on the numbers, which everyone knew. That Apple products inspired strong brand loyalty and that the brands coalesced to form a private ecosystem encircled by the coveted “moat” was also common knowledge.

I don’t remember if Buffett mentioned “intrinsic value” when subsequently discussing his reasons for investing in Apple. I suspect he did. It’s a term I find mostly bemusing, and it’s one analysts invoke frequently. “The shares trade below intrinsic value,” the analyst declares, as if the calculation is anchored in concrete and that what he knows as fact everyone will eventually discover. More often, intrinsic value is determined by the qualitative. I wouldn’t be surprised if Buffett’s “intrinsic value” and his belief the shares were trading at a discount to “intrinsic value” were predicated on the following logic: “We all think Apple will continue to perform, but I’m convinced Apple will perform better than most investors expect.” The approach works for those with the most finely honed instincts, but it creates an intractable problem for those keen to replicate Buffett’s success. Analysis begins with a premise, and rarely is it undertaken to disabuse the premise. Analysis is mostly an exercise in self-confirming data mining and positive self-talk.)

Berkshire Hathaway’s domestic stock portfolio comprises 36 company stocks valued at $260 billion. The Japanese trading houses add another $25 billion, give or take. Berkshire’s 54 million shares of Chinese EV maker BYD add around $3 billion. Tally it up, and Berkshire’s equity portfolio is valued at around $290 billion.

To put the Berkshire’s stock into perspective, we find the largest actively managed mutual fund is the American Funds Washington Mutual Fund (RWMGX) with $184 billion of assets. The largest actively managed ETF is the JPMorgan Equity Premium Income ETF (JEPI) with $38 billion of assets. (There are a few indexed mutual funds and ETFs, based on the total market or S&P 500, that are larger than Berkshire’s stock portfolio, but only a few.)

Berkshire has also squirreled away a Ghazipur Landfill’s heap of dry powder composed mostly of $348 billion in U.S. Treasury bills. To hold a third of the market value of a $1 trillion equity market cap company in money market instruments is to imply in unequivocal terms, I know better than you, and I know it a lot better.

And, of course, Berkshire is an operating company — an agglomeration of operating companies, actually. I count 65, but I could be wrong. I would still wager the count is north of 60.

Berkshire Hathaway Wholly and Majority Owned Businesses by Segment

Insurance and Reinsurance

GEICO — Auto insurance

General Re (Gen Re) — Global reinsurance (property/casualty, life/health)

National Indemnity Company — Commercial insurance and reinsurance

Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group — Large-scale reinsurance

Berkshire Hathaway Primary Group — Specialty and commercial insurance

United States Liability Insurance Group (USLI)

Berkshire Hathaway Assurance — Municipal bond insurance

biBerk — Small business insurance

Central States Indemnity

Alleghany Corporation — Insurance holding company (Transatlantic Re, RSUI, CapSpecialty, etc.)

Railroad, Transportation & Logistics

BNSF Railway — Major North American freight railroad

BNSF Logistics — Supply chain and logistics services

XTRA Corporation — Trailer and intermodal equipment leasing

McLane Company — Wholesale distribution (grocery, foodservice, beverage)

Utilities and Energy (Berkshire Hathaway Energy and Subsidiaries)

MidAmerican Energy Company — Electric and gas utility (Midwest US)

PacifiCorp — Electric utility (Western US)

NV Energy — Electric and gas utility (Nevada)

Northern Powergrid — Electricity distribution (UK)

Northern Natural Gas Company — Gas pipelines (Midwest US)

Kern River Gas Transmission Company — Gas pipelines (Western US)

BHE Renewables — Solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric generation

AltaLink — Transmission (Alberta, Canada)

BHE U.S. Transmission — Transmission assets (US)

CalEnergy Resources — Geothermal energy

BHE GT&S — Gas transmission/storage (Eastern US)

HomeServices of America — Real estate brokerage (pending sale as of 2025, but still owned)

Other BHE subsidiaries: Metalogic Inspection Services, Intelligent Energy Solutions, Integrated Utility Services UK

Manufacturing

Precision Castparts Corp. — Aerospace and industrial components

Marmon Holdings — Industrial products (includes Union Tank Car, Marmon Foodservice, etc.)

Lubrizol Corporation — Specialty chemicals and additives

Benjamin Moore & Co. — Paints and coatings

Johns Manville — Building materials

Shaw Industries — Flooring and carpet

CTB International — Agricultural equipment and systems

Forest River — RVs, buses, cargo trailers

MiTek Inc. — Building products and engineering

IMC International Metalworking Companies — Metal cutting tools

Fruit of the Loom — Apparel (includes Russell Athletic, Vanity Fair Brands)

Garan, Inc. — Children’s apparel

Fechheimer Brothers — Uniforms

Brooks Sports — Running shoes and athletic apparel

Justin Brands — Western and work boots (Justin Boots, Tony Lama, Nocona, Chippewa)

Scott Fetzer Company — Diversified manufacturing (includes World Book, Kirby, etc.)

Duracell — Batteries

Acme Brick Company — Bricks and building materials

Clayton Homes — Manufactured and modular homes

Retailing

Nebraska Furniture Mart — Furniture and appliances

RC Willey Home Furnishings — Furniture and appliances

Star Furniture — Furniture

Jordan’s Furniture — Furniture

See’s Candies — Confectionery

Ben Bridge Jeweler — Jewelry retail

Borsheims Fine Jewelry — Jewelry retail

Helzberg Diamonds — Jewelry retail

Pampered Chef — Kitchenware and home products

Oriental Trading Company — Party supplies and novelties

Food & Beverage

Dairy Queen — Ice cream and fast-food restaurants

Aviation & Services

NetJets — Fractional jet ownership and private aviation

FlightSafety International — Pilot training and simulation

Business Wire — News distribution and regulatory disclosure

Berkshire Hathaway Automotive — Auto dealerships

Pilot Travel Centers (Pilot Flying J) — Truck stops/travel centers (majority stake as of 2024)

Charter Brokerage — Logistics and customs brokerage

Media

WPLG-TV — Television broadcasting (Miami)

World Book, Inc. — Encyclopedias and educational products (via Scott Fetzer)

So, the trillion-dollar equity market cap is composed of a third publicly traded equities, a slew of wholly owned operating businesses, and a third cash. The time has come to cease bolting on and incorporating and begin transitioning to maximizing the value of what you have. Here, I expect Greg Abel to have the upper hand, given he’s a hands-on, operational guy.

The timing and duration of the Apple investment is commendable but hardly an outlier endeavor. Many investors have held Apple shares as long and longer and fared as well and better. The Japanese trading houses were recondite to most investors, and they have performed admirably, but the part relative to the whole amounts to a rounding error.

Constellation Brands, Domino’s Pizza, Pool Corp., Sirius XM, Verisign, there’s nothing there, and if there is, the positions are minuscule, as is the impact on Berkshire’s value. Chubb is a well run conservative insurance company. Progressive Corp. has generated 5 percentage points more CAGR over the past 40 years.

Maybe Buffett performs another in-your-face coup with the obvious. Instead of Apple, maybe this time it’s Tesla (TSLA). Berkshire buys $40 billion worth of Elon Musk’s baby, and the investment proves just as remunerative as Apple.

When do you get out? You can argue Berkshire has hung on too long with The Coca-Cola Co. Coca-Cola generated a CAGR more than twice that of the S&P 500 over the first seven years Berkshire owned it. In the past 30 years, Coca-Cola’s CAGR has trailed the S&P 500 by two percentage points. What are the odds $3 trillion-dollar market cap Apple will continue to outperform the S&P 500? (The Berkshire position was established when Apple shares were valued in the $600 billions.)

What about the all-in purchases?

Berkshire thought the $11.6 billion of Alleghany Corp. in 2022 was a good fit. Alleghany, a P&C insurance company, shares many attributes, if not the ethos, of Berkshire’s insurance segment. Add it to the mix. That makes insurance company number 10. More interest-free float is on hand (as if access to low-cost money is an issue).

Berkshire Hathaway bought an initial 38.6% stake in Pilot Travel Centers truck stops in 2017. In early January, Berkshire bought the enterprise in full, spending $13.6 for an all-in acquisition, but not before a publicly aired contretemps. (Pilot Travel Centers’ former owners, Haslam family, sued Berkshire in a complaint that accused the conglomerate of using so-called pushdown accounting at Pilot Travel Centers without authorization.)

Precision Castparts, a 2016 Berkshire acquisition, has been OK and then disappointing. Buffett himself has repeatedly described the 2016 acquisition—at a cost of $37 billion—as a mistake, admitting he overpaid based on overly optimistic profit projections. In 2020, Berkshire took a nearly $10–11 billion write-down on the investment, reflecting a sharp decline in the company’s value due to weakened aerospace demand during the pandemic years.

Berkshire agreed to acquire Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway in November 2009. The acquisition was completed in February 2010. The total value of the deal was approximately $44 billion, which included $26.5 billion in cash and stock for the shares Berkshire did not already own, plus the assumption of about $10 billion in BNSF debt. This remains the largest acquisition in Berkshire’s history.

A winner. Warren Buffett and Berkshire’s management have described BNSF as an “irreplaceable” asset, consistently generating strong, reliable cash flows and providing stable, tax-efficient returns. I’ll take him at his word, though BNSF needs a little shaping up.

In recent years, BNSF’s earnings and revenue growth have been stable but have trailed behind its peers, notably Union Pacific (UP) and Canadian National (CN), which have generally reported higher operating margins and more aggressive cost-cutting. For example, Union Pacific has consistently posted operating ratios in the mid- to low-60% range, while BNSF’s ratio, though improved, has typically been slightly higher, and higher than the industry average.

There’s nothing egregiously wrong with these purchases, nor is there anything sublimely right. I’m sure they add more than they subtract.

But what’s the point of owning the following stocks? Each accounts for less than 1% of portfolio value. In total, they account for less than 6%. Do these lesser holdings constitute a training portfolio for Ted Weschler and Todd Combs? Or would it be too embarrassing to buy another $15 billion worth of Treasury bills?

Constellation Brands (STZ)

Mastercard (MA)

Amazon (AMZN)

Aon Plc (AON)

Domino’s Pizza (DPZ)

Ally (ALLY)

T-Mobile (TMUS)

Liberty Media Corp. (LLYVK)

Charter Communications (CHTR)

Louisiana-Pacific Corp. (LPX)

Pool Corp. (POOL)

Formula One Group (FWONK)

Heico Corp. (HEI)

Diageo Plc (DEO)

Jeffries Financial (JEF)

Liberty Media Latin America (LILA)

Lennar Corp. (LEN)

Atlanta Brave Holdings (BATRK)

(Sidebar: Charlie Munger: “The idea of diversification makes sense to a point — if you don't know what you're doing. If you want the standard result and don't want to end up embarrassed — then of course, you should widely diversify. But nobody is entitled to a lot of money for holding this view. It's like knowing 2 plus 2 is 4. Any idiot can diversify a portfolio.” Perhaps Charlie should have added that his observation holds at the other end of the bell curve: Any genius can diversify a portfolio.)

Two forces oppose each other in determining Berkshire’s equity market value: the conglomerate discount and the Warren Buffett cult-of-personality premium. I suspect the latter continues to hold sway, which I see as detrimental to outside shareholder interest. To continue to bolt on new additions at this point only contributes to the conglomerate discount, which will soon enough prevail.

But a-bolting-on we will go. Berkshire Hathaway recently requested an SEC exemption from immediate disclosure — known as “confidential treatment”—for at least one of its stock purchases. According to a May 2025 report, Berkshire is buying an undisclosed stock under confidential treatment, which allows it to accumulate its position without revealing the purchase to the public until the accumulation is complete.

Who could it be?

Occidental Petroleum gets a lot of run. Berkshire owns 265 million of Occidental’s 942 million outstanding (fully diluted) shares. This leaves 677 million outstanding. Occidental shares trade around $41. If Berkshire offered a 15% premium and investors accepted it, the remaining equity could be bought for $32 billion. Berkshire would also need to assume about $24 billion worth of Occidental long-term debt. An all-in acquisition would value the transaction at $56 billion. There is $8.5 billion of outstanding preferred stock, but that’s Berkshire’s. I’ll assume Berkshire’s cost basis per share is $52, so Berkshire has $19 billion tied up in common equity already.

Based on my pen-to-cocktail-napkin calculation after draining a second Blue Sapphire martini, Berkshire can be the proud owner of Occidental Petroleum for $83.5 billion. (I’m not subtracting the $2.5 billion of cash on Occidental’s books.)

Who is excited about that?

Perhaps the fish is bigger. Berkshire was granted confidential treatment last year while it accumulated 26 million Chubb Limited shares for $6.7 billion. Berkshire subsequently added a million shares to the tally. And a big fish it would be, indeed. Chubb’s equity market cap is $115 billion.

Chubb’s a well-run insurer, though the Berkshire pantry is already larded with well-run insurers. Chubb would mean more coveted float and more free cash flow. To do what with? Buy more Constellation Brands, more Sirius XM, more Treasury bills?

Similar to Liam Neeson, who famously declared in a very forgettable film, “I do have are a very particular set of skills. Skills I have acquired over a very long career. Skills that make me a nightmare for people like you.” Buffett, too, has a “very particular set of skills. Skills… acquired over a very long career.” We all know the principal skill: To deftly allocate capital to other people’s businesses to a degree never before seen.

Embedded in the set is another less conspicuous Buffett skill: A knack for surrounding himself with competent people with the complementary skills that enable Buffett to concentrate on his particular skill set. Buffett has rarely fired a leader of a Berkshire Hathaway operating business. When changes have occurred, they have usually been the product retirements, deaths, or the manager’s decision to leave rather than be terminated for cause.

Throughout his six-decade tenure as CEO, Buffett became renowned for his hands-off management style, granting significant autonomy to the managers of Berkshire’s subsidiaries. This approach is a hallmark of Berkshire’s decentralized culture and Buffett’s ability to choose his business leaders.

I expect CEO-in-waiting Greg Abel — a 25-year Berkshire executive — to act similarly, but better. Abel’s skill set differs from Buffett’s, and thank goodness for that. Abel is an operations man. His forte is attending to the dirtier work of running businesses (which includes the skill to allocate capital within the businesses).

I suspect I was in the minority, but I was pleased when Buffett announced earlier this month that he would step down from the CEO role. A masterly investor/capital allocator is no longer the preeminent skill needed to drive Berkshire’s future success.

Berkshire Hathaway v. the S&P 500 (2005 — Present)

Berkshire Hathaway v. the S&P 500 (1985 — 2005)

Buffett’s nonpareil investing skill has been negated to a great degree by the insurmountable physics of it all. For it to matter, individuals will deal in increments of tens of thousands of dollars, institutions in tens of millions. Berkshire will deal in increments of tens of billions. Given that we (the individuals) fish in an ocean and Berkshire is confined to a lake, the possibility for us, even when handicapped by our relatively meager abilities, to outperform the master is worth considering. Aside from Apple, whose success for Berkshire distills mostly to magnitude, I fail to see sublime mastery at work with the domestic stocks Berkshire Hathaway has purchased over the past 10 years. It’s the stuff of any large cap blended mutual fund. (And the “whoops, sorry about that” quick turnaround purchase and sale of Taiwan Semiconductor two years ago gives cause for pause.)

Could another hiding-in-plain-sight stock to absorb $40 billion be in the waiting? Could be. Maybe it’s the aforementioned Tesla after Buffett rebrands it mentally as a consumer/tech instead of a transportation company. Is Meta Platforms (META) undervalued, a moated company with a self-contained Apple-like ecosystem? The latest mystery purchase will be unveiled soon enough.

I’m a Berkshire investor, and I, for one, welcome the change at the top. We all have a place and a time. We also have an expiration date. Everything has an expiration date. What worked best no longer works best. Circumstances always change. The right person then isn’t necessary — and mostly isn’t — the right person now.

Buffett exudes a wise avuncular personality. He’s never belligerent, always accommodating. He’s self-effacing. He presents as an everyman. Buffett disarms with charm, and charm is a most effective deflector of criticism.

And rarely is Buffett criticized, and if he is, the criticism is tempered by a panegyric preamble. (My criticism has been tempered by a panegyric preamble.) I expect Greg Abel’s treatment will be considerably less deferential and become even less so as time passes. What investors overlooked with Buffett, they won’t overlook with Abel — namely, that $348 billion cash account — and that’s a good thing.

I understand that Berkshire is a conglomerate unlike other conglomerates — a point Buffett extols: Berkshire doesn’t pay for acquisitions with new stock issuance with rare exception. It rarely overpays. The internal cash flows and insurance float create a low-cost source of capital to grow the member businesses and capitalize on external opportunities when they arise. Berkshire’s decentralized organization enables strong-willed, ambitious entrepreneurs and managers to thrive. Entrepreneurs and managers are able to plan with a time horizon unperturbed by Wall Street’s “short-termism.”

(Sidebar: Wall Street “short-termism” is mostly a canard. If your honest and explain your business and capital allocation plans and

It’s all good for those inside, but what about those of us — the passive shareholders — on the outside looking in? Theoretically, the argument is persuasive, but is it as productive as we’ve been led to believe?

General Electric (GE) was a conglomerate and was once lauded for being one. Its CEO, Jack Welch, was the talk of Wall Street and revered nearly as much as Buffett. Welch was even coronated as “Manager of the Century.” GE would continually meet and beat ever-rising revenue and earnings guidance during Welch’s tenure. GE stock generated a 21% CAGR over Welch’s 20-year run (1981 to 2001).

A few years later, the truth emerged. What was perceived to be an impenetrable medieval fortress was revealed to be lean-to built on bamboo stilts anchored in sand. Without government interceding, GE would have been laid to waste during the 2008 financial crisis. The 17 years following Welch’s departure was a walk in the desert for GE shareholders, producing a negative 4% CAGR.

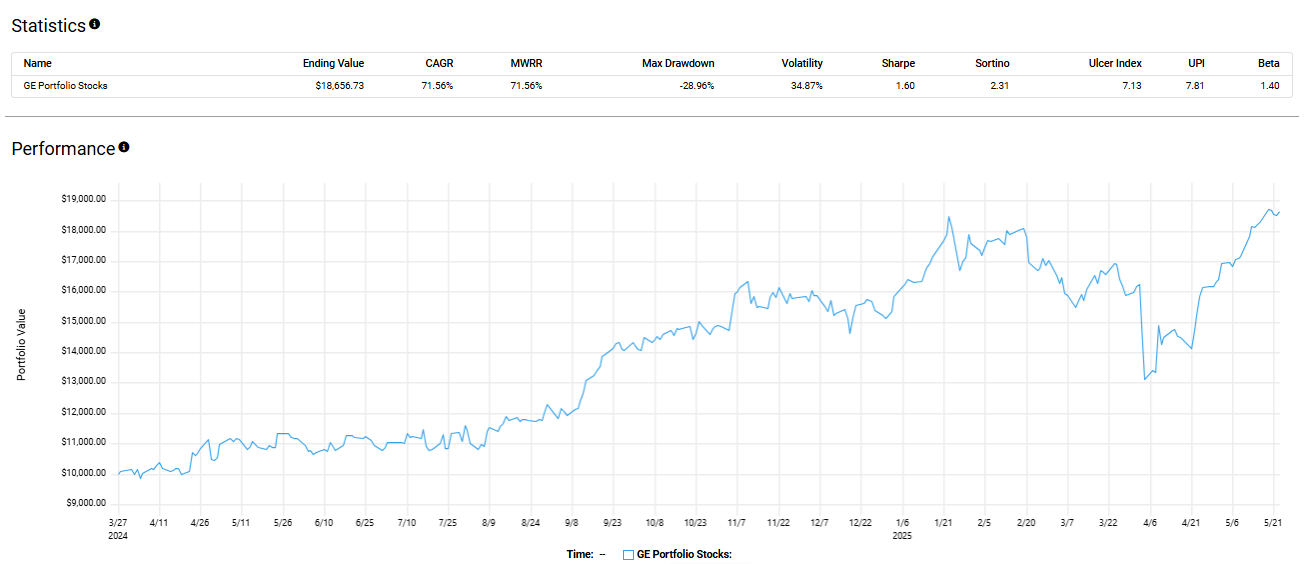

In 2018, current GE CEO Larry Culp stepped in and deconglomerated. The healthcare division was spun off into GE HealthCare Technologies (GEHC) in 2023. A year later, what remained was bifurcated into GE Aerospace (GE) and GE Verona (GEV), the energy-generating division.

The healthcare company has stumbled along since its debut as a publicly traded entity. It has generated a 6% CAGR. The other two companies have run wild as if freed on a jailbreak.

A 50/50 allocation between GE and GEHC generated a 76% CAGR until March 2024 when GE further de-conglomerated into a triptych. A portfolio allocated a third to each stock has generated a 71% CAGR.

I’m not suggesting Buffett will leave a mess — a la Jack Welch — for his successors to mop up. At the very least, it would make for an uncomfortable work environment. (Buffett still plans to be in the office regularly.)

Would it be unreasonable to split Berkshire into an operating and investment company? One company could comprise the insurance companies and all the publicly traded investments. The other could comprise everything else, with perhaps a further atomizing into industrial and consumer product components. (I suspect the consumer products companies generate the lowest returns.) I like the idea, along with the notion of returning excess capital — through dividends and share repurchases — to shareholders.

Buffett has planned the transfer intelligently, though that was to be expected. To step down upon death would have been most inconsiderate. At 94 (soon to be 95 in August), he has already pushed the boundaries to the limit. Perhaps he expects a deconglomeratizing of Berkshire to occur after his death. At the least, I would expect he knows a dividend has to be forthcoming. As to the counsel he has given his two sons and daughter on voting that 30% interest, we can only speculate.

Buffett announced recently that he will take to the sidelines come the May 2026 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting. He will sit on the main floor with the other Berkshire directors. This is welcomed news for serious shareholders watching from afar. We can hope the days of the Berkshire shareholder (“B” shares) sending his well-rehearsed precocious 12-year-old to the mic to ask a life question of Buffett that should be addressed to mom and pop are over. And if we also see the end of the nine-minute shareholder soliloquy composed of a third Buffett encomium, a third autobiography, and a third a six-part question where the first five parts are forgotten by the time the sixth is reached, all the better.

I understand the dynamics of it all. Buffett will remain ruler supreme — fortified by the chairmanship and the 30% voting interest — for the time being. I suspect he will retain his regality until he dies, and perhaps after, at least for a while. And if I don’t like it, lump it or sell my investment. Buffett would never word it like that, though many of his acolytes would.

All I know with the highest probability (certainty being a fiction in our world) is that when Buffett goes, his premium goes with him. Even if he is around, the premium could dissipate as investors acclimate themselves to him no longer helming the ship as CEO. If the status quo remains, so does the conglomerate discount. Best to get ahead of the curve. I would prefer Greg Abel make a few publicly un-Buffett moves at the outset, with Buffett maintaining his silence. It would go a long way to winning investor confidence to Abel’s side and to demonstrate that it will no longer be business as usual. I’m willing to stick around and see how it all plays out.