SVB Financial Was Only the Symptom of an Intractable Disease

And why more rules and regulation won’t make a damn bit of difference to preventing the next banking meltdown.

I’ve been in the investing, advising, and financial writing business for thirty-five years and counting. Over those three-and-a-half decades, I’ve recommended and/or owned four bank stocks: Cullen/Frost Bankers (NYSE: CFR); Community Trust Bancorp (NASDAQ: CTBI); Wells Fargo (NYSE: WFC); and Peoples United Financial, now part of M&T Bank Corp. (NYSE: MTB).

The first two – Cullen/Frost Bankers and Community Trust Bancorp – were “OK” investments, with some share-price appreciation and discernible dividend growth.

The fourth, Peoples United, was a middling investment with an asterisk.

Peoples United probably would have been a decent investment had it not been for its relentless and annoying acquisition strategy. It’s not that the acquisitions were egregious. Peoples generally paid a reasonable price. The problem for me was that Peoples always paid with stock. Peoples might acquire a decent local bank, but the benefits were muted by stock dilution. Peoples’ earnings and dividends would creep higher each year, and so, too, would the share price – ”creep” being the operative word; that’s all it did.

I mostly ignored Peoples United over my multi-year holding period because of its four percent dividend yield and consistent, creeping dividend payment, but when M&T announced its intentions and Peoples’ share price spiked, I sold it all in a heartbeat. (I had no interest in owning, then or now, M&T Bank Corp.)

As for Wells Fargo, one of its passbook savings accounts would have been a better investment. Wells Fargo has been mostly an operating mess since the 2008 financial crisis.

As if opening fraudulent accounts wasn’t enough, Wells Fargo doubled down and then fessed up to harming sixteen million Wells Fargo customers in its managing of auto and mortgage loans. Wells Fargo agreed to settle with the Federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) for $3.7 billion. Warren Buffett professes to value reputation above all else. Why he hung around with Wells Fargo (for Berkshire Hathaway’s account) as long as he did, I don’t know. Why I hung around as long as I did was a case of monkey-see, monkey-do.

Will there be a fifth bank recommendation for others or a bank investment for my account? Never say never, but...I’ll say it anyway – never.

I have been permanently dissuaded by experience and my subsequent conviction: The business of banking is intractably faulty.

My opinion is not predicated on some mob-following recency. It was formed long before the SVB Financial (NASDAQ: SIVB) fiasco, which is really no more than a fiasco. From my vantage point, I see nothing duplicitous or criminal on SVB’s part. It all seems innocent enough, although a bit naive for an experienced bank management team. Bank management simply did a poor job of risk management, specifically mismanaging liabilities and assets – fixed long-term assets against variable short-term liabilities. Interest-rate risk is real. But keep in mind that banking at its most basic is a business of borrowing short-term and lending long-term. (Did anyone else raise an eyebrow when Harvard intellectual colossus and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said that SVB Financial “committed one of the most elementary errors in banking: borrowing money in the short term and investing in the long term”? Dude, that’s the business model.)

Banks are regulated to the degree of public utilities. Though, unlike a public utility, a bank doesn’t enjoy the benefit of a captive audience. You might dislike and distrust your electric company, but the most you can do is grumble about it. Dislike or, worse, distrust your bank, and you’re outta there, as SVB Financial’s instant insolvency once again proves. You have plenty of banking options.

Banks, you could argue, are regulated to an even greater degree than a public utility. The bowl of alphabet soup regulatory agencies is stupefyingly large: the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB); the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), the Federal Reserve System (FRS), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). I’m sure I’m leaving out someone, and probably many “someones”.

Stupefying because I’m also of the mind that regulators do more harm than good.

Raise the cost of doing business, which regulation does, and you retard competition. Regulation further entrenches the status quo. The largest, most established companies are those most welcoming of regulation for the very reason that regulation retards competition. Regulators, in turn, are frequently captured by those they regulate – so a double-win for the big guys. The regulators are then written to favor the status quo. (University of Chicago economist George Stigler is a widely cited expert on regulatory capture.)

(Sidebar: The SEC has done more harm than good. Without argument, it has raised the cost to deliver financial advice and to research companies. The SEC focuses too intently on the least consequential and lowest-hanging fruit – paperwork, and the required filing thereof. Paper filing and mandate jargon, which are ever-expending, have reduced financial reports to the unreadable. The reports have been so densely infused with boilerplate CYA language, such as the language you will find in the “Risk” section, which, when you examine the postmortem, you discover the “risk” that actually killed the patient was never listed. A 10-K should be no longer than twenty-five pages; a 10-Q no longer than ten. Brevity being the soul of wit, and the most efficient conveyor of usable information. When it matters, such as in the obvious with Bernie Madoff, the SEC is nowhere to be found.)

Some – mostly those who stridently support the gold standard and a laissez-faire market economy, which has never existed – blame fractional-reserve lending as the culprit for banking’s inherent instability. To be sure, a full-reserve system – where each loan is 100% backed by money – would be less risky than a fractional reserve system. But life isn’t about minimizing absolute risk. It’s about accepting risk relative to an expected benefit.

Fractional-reserve banking has its benefits. Because fractional-reserve banking offers banks more opportunities to profit, fractional-reserve banking lowers the cost of banking for most consumers (free checking, no minimum deposit requirements, immediate money access, free money transfer services), which you would unlikely get in a full-reserve system. A fractional-reserve system also opens the market to more consumers; thus, it is a more egalitarian capital-access system than a full-reserve system. I have no trouble with the concept.

When it all goes wrong, as it did in 2008, the Federal Reserve ensures fractional-reserve lending morphs into one-hundred-percent reserved outcomes. The Federal Reserve ensures everyone is made whole when it all goes systemically wrong, shareholders and bondholders being the exception. So knowing an entity will make it mostly right when it all goes wrong, promotes excessive risk-taking, accompanied by a lax attitude toward the excessive risk. Human nature being what it is.

Moral hazard is the real intractable problem, with the Federal Reserve being the primary source of the problem. I might be an imbecile, but what if morons are leading the way?

The Fed’s inability to acknowledge reality set the table for what’s occurring today. In June 2021, the CPI showed a 5% year-over-year increase, accelerating from a 1.7% annual pace only three months earlier. Rather than throttle back from the COVID-era policies of near-zero interest rates and copious asset purchases, the Fed maintained the benchmark funds rate at 0% to 0.25% while expanding Reserve Bank credit by $1.19 trillion over the subsequent nine months.

And human nature being what it is, we acquiesce to incentives.

We had been in a forty-year bond bull-market run until last year. The bull market having begun in 1981. Many pundits predicted and continually predicted that the bull market would find itself at a nearby abattoir soon after the 2008 financial crisis was no longer a crisis. The Fed would soon need to raise interest rates and sell securities to tamp down the 1970s-era inflation that was sure to follow.

But it didn’t, at least for a due-diligence relaxing amount of time. It took fifteen years before it finally happened last year. The market had finally choked on a massive influx of money (after COVID, this time). Even then, one could understand why one would assume it would be transitory. Two generations of Americans had never experienced a disruptive inflation. Most of the country had become inured to the prospect. And, hey, 1970s-era inflation never emerged after the massive monetary injection following the worst financial crisis since 1929.

But it’s all transitory.

I have no doubt that many bankers last year thought it would be only a short time before they were again borrowing at twenty-five basis points and lending at three-hundred basis points. We’ll be back to Nirvana in short order. After all, how often had “wolf” been cried on inflation over the past decade? When no wolf appears you become anesthetized to the warning.

And if deposits are outrunning lending opportunities in the meantime? Let’s load up on grade-A long-term paper. It is, after all, grade-A paper. SVB Financial loaded up this type of paper as its deposits soared and investment opportunities dwindled.

A few in the commentariat brigade have lobbed charges of “greed” or “avarice” at SVB’s management. (Keith Fitz-Gerald, a trader and principal of the eponymous Fitz-Gerald Group, lobbed both recently when interviewed by CNBC. Says Mr. Fitz-Gerald, “I think that the greed and avarice that has long been present in Silicon Valley has come home to roost.”) Of course, it’s always the other guy who is greedy or avaricious. Me, I’m just ambitious and opportunistic. And if it goes all wrong, only unfortunate.

SVB management was neither greedy nor avaricious in running the business. On the contrary, SVB management was an exemplar of banking by the book. Management followed a conservative policy of acquiring the safest assets as deposits soared. Management acted exactly as those who rewrote the rulebook after the 2008 financial crisis would have them act. SVB was a boring, conservative bank that invested its rising deposits in Treasury debt and mortgage-backed securities.

Yes, we can point an accusatory finger in SVB management’s direction and scold it for ignoring interest-rate risk. SVB management, in turn, could point its own accusatory finger at the Federal Reserve and say, “Well, these guys are buying billions of dollars of long-term Treasuries and MBS each month. Why shouldn’t we be buying them?” Many other bankers are sure to have done the same – go long on long-term investment-grade debt. These guys run in the same circles, after all.

I offer another interest-rate tidbit. Perhaps you remember when many pundits were prognosticating better days for banks should interest rates rise. Great, they told us. The higher the lending rate, the greater the net interest income, the wider the net interest margin.

I was always skeptical about the narrative. Absolute interest rates mean much less than relative interest rates to a bank. The shape of the yield curve is what matters. Borrow short-term at twenty-five basis points, lend at three hundred basis points, Nirvana. Borrow at three hundred basis points, lend at five-hundred points, OK, for now, I suppose. (Let’s also remember demand curves are downward sloping: the higher the cost, the less the demand.) Lend long-term at three percent and have market yields rise to five percent, now you’re courting insolvency.

The prospect of insolvency probably would have come and gone, like the wake of a passing motor boat, if everyone kept quiet, kept his head down, and kept pushing forward as business usual. Some, though – and one in particular – were unwilling to keep quiet and keep pushing. Peter Thiel, the very public founder of Founder’s Fund, put a bee in everyone’s bonnet when he very publicly advised companies with SVB Bank deposits to pull money from SVB. When a few prominent companies, heeded Thiel’s words, the remaining depositors were forced into a game of Prisoner’s Dilemma. We know how it played out.

In hindsight, it didn’t matter, now that the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve said all depositors would be made whole. I also found it interesting that less than 3% of SVB’s depositor base had funds under the $250,000 insurance threshold. That suggests that SVB had a relatively wealthy and presumably sophisticated depositor clientele.

Moral hazard is the petard that implodes a bank. Moral hazard is the reason the financial sector gets itself into quandaries that border on collapse every ten to fifteen years.

SVB management was addled by the moral hazards the banking system is suffused with by all the regulations. (This isn’t to excuse SVB management, not by any means. They are still worthy of all the blame. They are yet another example of why you should side with wise management over smart management.) Regulation dulls the individual’s due-diligence imperative. Federal Reserve monetary policy all but dictates how your bank operates. Should you be forgiven for misdirection or inertia? And now that the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve have set the precedent of ensuring all depositors are made whole, moral hazard has been ratcheted a notch higher. Why bother with due diligence at all?

Perhaps the genesis of moral hazard is found in the business construct. Banking is an intangible-asset/intangible-liability business. It’s all predicated on trust. Trust is the bedrock of a bank’s existence. As soon as trust is lost, the porticoes crumble and then the whole edifice collapses. Too many bankers are financially and emotionally inured to this reality. They have a cavalier attitude toward trust and its importance.

We have a precedent.

I don’t see it as a coincidence that all the major Wall Street investment banks imploded soon after switching to a C-corp. business structure from a partnership structure. A C-corp. structure is limited liability, a partnership structure is open-ended. A C-corp. structure incentives risk-taking. You get it right, you profit. You get it right with leverage, you profit in multiples. You get it wrong in a C-corp., you lose, but your loss is restricted to the bank’s capital structure. You disgorge little. All those leverage bets you made in the past, and for which you were compensated (bonuses, cashed-in stock options), are yours to keep, even if you have left a landscape of ruin in your aftermath.

If a leveraged bet goes wrong in a partnership, on the other hand, there is gonna be some disgorging on your part. If you have an active role in business operations, you’ll be subject to personal liability for the actions of the business. Yes, you reap the rewards when it all goes wondrously right, but also the losses when it all goes terribly wrong. Sounds to me like a good business structure for honing attentiveness and maintaining trust.

Investment bankers used to be aware and attentive to this dynamic. Many investment banks survived decades that could be measured as a century when they were organized as partnerships. Most went to pot within a decade after restructuring as a C-corp. Had it not been for Fed and Treasury Dept. intervention in 2008, Wall Street would have been cleared of its fabled investment banks.

If the business involves intangible assets and multiples of leverage, perhaps a C-corp. structure should be off-limits. At the least, it would temper the systemic damage moral hazard promotes. Unfortunately, the odds of that occurring are practically zero.

Post Script: The Worst Bank in the World?

While I’m on the subject of banking and venting on banking, why not wander off the path to vent on a specific bank I’ve disliked for years?

I have never owned nor recommended its shares. Why this monstrosity still exists, I don’t know.

Like the proverbial coward, this bank has died a thousand deaths only to emerge from the grave like some Wes Craven-inspired zombie. It just won’t stay down. I know why: too many politicians and government regulators are too tightly tethered to this zombie to let it stay down. This exemplar of the walking dead should have had a stake driven through its heart in 2008. But no, here it is

I refer to Citigroup (NYSE: C).

If you’re interested in a bank with an unparalleled ability to burn through capital and destroy shareholder value, here’s your bank. I dislike this bank. I dislike its history, I dislike everything it represents, even though I’ve never owned its shares.

If there is a systemic crisis, a macro dog pile dumped somewhere, you’ll probably find Citigroup’s foot right in the middle of the pile, or you’ll find its fecal-smeared footprint nearby.

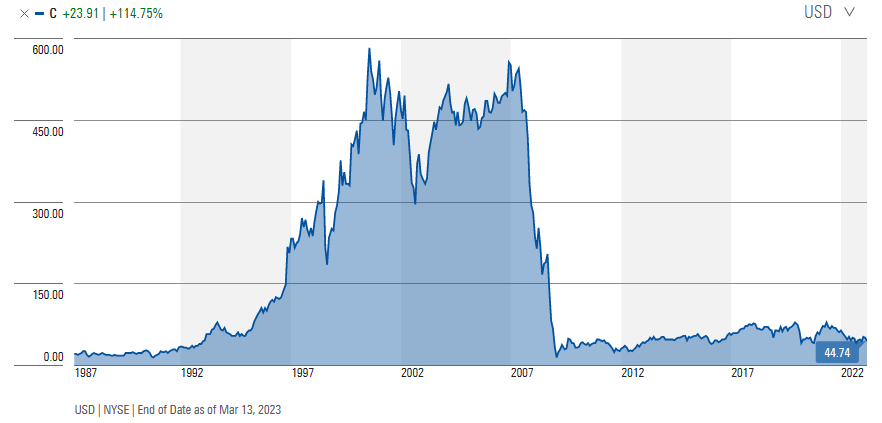

It has never mattered who was at the helm – Walter Wriston, Sanford Weill, John Reed, Robert Rubin – Citigroup has been a terrible investment. Here’s the visual evidence.

Citigroup was trading at around $20 in 1987. It’s trading around $47 today. You’re looking at 2.5% annualized share-price appreciation. But look at what you had to endure if you were a long-term investor.

You might argue that Citigroup has been given a new lease on life post-2008. The zombie has been reanimated, leopards change their spots, or whatever change-of-character cliché you prefer. Fair enough.

Had you bought Citigroup shares at the March nadir in 2009 (and you wouldn’t have), you’d be holding an investment that has appreciated at an 8.5% average annual rate. (An S&P 500 ETF appreciated at a 12.7% average annual rate. An unfair comparison? OK. Let’s say the choice was between Citigroup and the Invesco KBW Bank ETF when it was birthed in November 2011. You would have doubled your money with the Invesco ETF compared to the Citigroup investment, but who am I to quibble?)

Citigroup’s quarterly dividend is $0.51 per share today. It was a penny in 2009, so a thumbs up to dividend growth. A thumbs up if we ignore that the quarterly dividend was $5.40 a share two years earlier. What the heck, let’s ignore it.

Perhaps I’m unfair. My opinion is too jaundiced by events that are no longer germane. Guilty as charged, but before you place a Citigroup buy order with your broker, you might want to glance at the chart below.

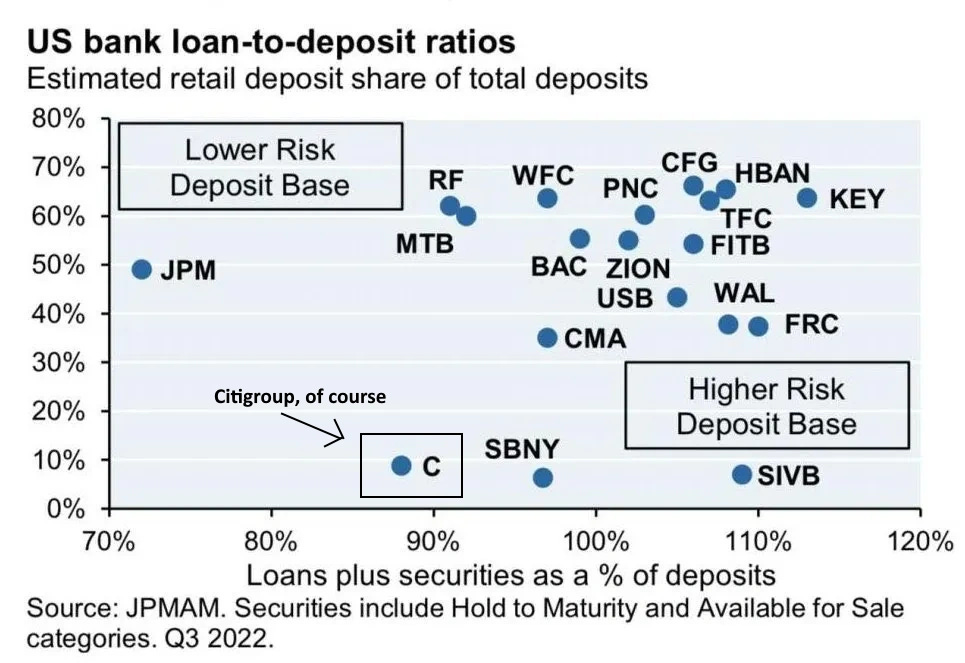

The bank-run risk appears highest with banks – SIVB Financial (NASDAQ: SIVB) and Signature Bank (NASDAQ: SBNY), for instance -- with business-focused deposits with a high invested capital per deposit.

I don’t know what percentage of Citigroup capital is invested in long-term securities. Nor do I know what percentage within that category is reported as “Held to Maturity (HTM)” or “Available for Sale (AFS)”. I don’t know because I’m too lazy to check and I don’t care. But if you’re a Citigroup investor, perhaps you might care and want to check.

DISCLAIMER: THE INFORMATION CONTAINED ON THIS WEBSITE IS NOT AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT ADVICE, AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO BE AND DOES NOT EXPRESS ANY OPINION AS TO THE PRICE AT WHICH THE SECURITIES OF ANY COMPANY MAY TRADE AT ANY TIME. THE INFORMATION AND OPINIONS PROVIDED HEREIN SHOULD NOT BE TAKEN AS SPECIFIC ADVICE ON THE MERITS OF ANY INVESTMENT DECISION. INVESTORS SHOULD MAKE THEIR OWN INVESTIGATION AND DECISIONS REGARDING THE PROSPECTS OF ANY COMPANY DISCUSSED HEREIN BASED ON SUCH INVESTORS’ OWN REVIEW OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION AND SHOULD NOT RELY ON THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN.